Last month, I wrote about a new streaming service that promises high-resolution, lossless audio. The main difference between Pure Audio and all the other streaming services that offer high-resolution, lossless audio is its focus on spatial audio. Fair enough.

What I want to do this month is expand on the second half of that article and attempt that always-challenging thing of having a nuanced argument on the internet. On one hand, I do the vast majority of my testing for SoundStage! Solo using high-rez or lossless audio. On the other, I do the vast majority of my non-testing, day-to-day listening using compressed, lossy audio. Please keep your pitchforks and torches fully sheathed until the end.

What is high-resolution audio?

Let’s first take a step back and figure out what we’re talking about. Basically, high-resolution audio is anything with a higher sample rate and/or bit depth than CD. That means greater than 44,100Hz and 16 bits. But what does that mean? Sample rate determines the highest frequency a digital signal can store. Thanks largely to a Swede named Harry and an American named Claude, we know that the highest frequency that can be recorded digitally is half the sampling frequency. For a variety of reasons (ahem, Sony), CD ended up with a 44.1kHz sample rate, which means it cannot accommodate frequencies above ~22.05kHz. Pushing the sampling frequency higher, so that it can encode frequencies beyond the audible range, has benefits. But as we’ll discuss in the next section, there are limits.

Bit depth determines the maximum dynamic range. As in, the maximum difference between the quietest and loudest recorded sounds. CD’s 16-bit encoding yields roughly 96dB of dynamic range. Generally speaking, this is more than enough for music playback, but for a variety of reasons, music is often recorded at higher bit depth. Increasing to “just” 24 bits, for instance, yields 144dB of dynamic range, which allows plenty of headroom for even the most energetic of performances.

For the early 1980s, CD’s 16-bit/44.1kHz audio was very impressive for digital devices in general and home audio specifically. Remember, this is just a few years after we went to the moon with less processing power than your average—well, literally any modern device has more processing power than what was used to go to the moon.

Usually, high-rez is discussed hand-in-hand with lossless. This refers to the data compression used to reduce file size. Pretty much all recorded audio you listen to is compressed in some way. Smaller files take up less storage space, and more importantly in this age, don’t require as much bandwidth to stream. Lossless refers to a type of compression that, when uncompressed by your device, results in a stream that is identical to the original source file before compression. Lossy compression, on the other hand, discards audio data. This means the version you’re hearing is different from the original. How well this lossy encoding is done is extremely important and technical, and probably deserves its own article.

With fewer constraints on data in these days of “unlimited” 5G wireless and 1Gbps fiber at home, larger, lossless files offer potentially better sound compared to poorly-encoded lossy files. Well-encoded lossy files, on the other hand, we’ll discuss in a moment.

This is the heavily truncated version, of course. I had a whole class in college, complete with a thick, expensive textbook, that went into the hows, whys, and wherefores of all this. As long as you get the basics, the rest should make sense.

More moreness is bestest?

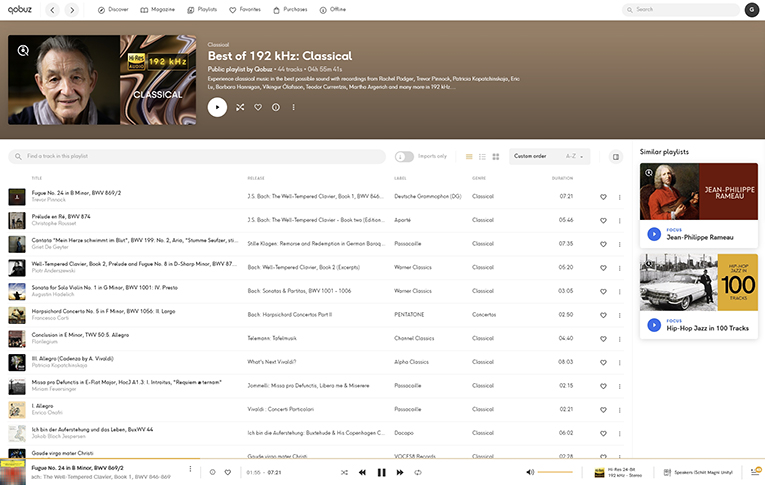

Many high-rez audio files have a sampling frequency of 96 or 192kHz, sometimes even higher, with a bit depth of 24 or more. Theoretically, this means you have more headroom for the overtones of instruments, greater dynamic range, and perhaps prevention of audio issues that, again in theory, can result from rolling off steeply above 20kHz. So on the surface, it seems obvious that everyone would want high-rez audio. More is better, right? Well, kinda. There are a few things to consider.

The first is that not all high-rez is high-rez. It depends on how, and on what medium, the original audio was recorded, or at the very least, what version of that original recording is available now. Much modern music, let’s say from the last 10 to 15 years, was recorded on equipment capable of higher-than-CD sample rates and bit depths. However, the early ’80s saw the introduction and eventual rise of digital audio, and every following year, more and more bands chose to record on digital equipment (though most recorded analog and only edited/mixed digitally). Either way, the end result was often a 16/44.1 file (or sometimes 16/48 or something close). It’s entirely possible that now that’s all that remains, and any “high-rez” versions of these recordings are just resampled, which isn’t really high-rez.

Before the digital transition, pre-1980s say, there were a variety of analog tape options. Being analog, they don’t have sample rates, but the better ones could record frequencies far higher than what’s possible with CD. Digital versions of these recordings, if encoded correctly, can definitely be high-rez.

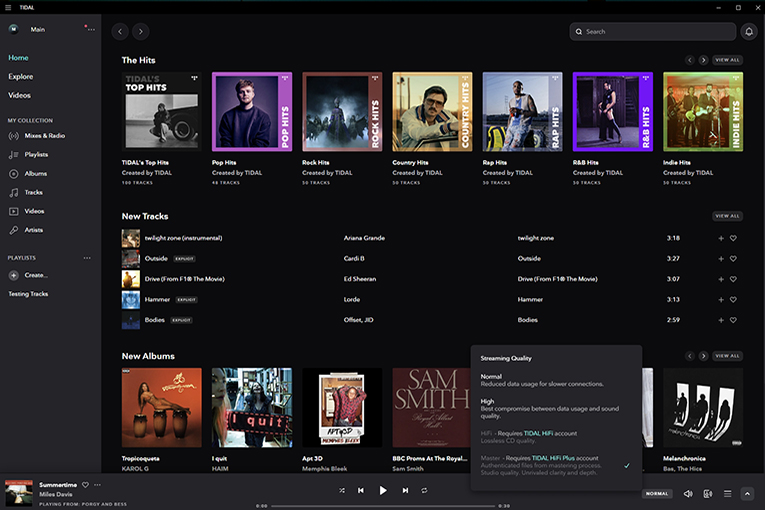

The second thing to consider is what you’re listening on. Can your device actually reproduce any of the added resolution? If you’re listening on a DAC through wired headphones, there’s a pretty good chance you’re getting high-rez (assuming your computer is set correctly). If you’re listening via Bluetooth, I have bad news. Bluetooth encodes the audio again, and most of the time, that means stripping out the high sample rate, the high bit depth, or both. Even codecs like LDAC that promise high-rez only do that under specific circumstances, circumstances you’ll rarely achieve in the real world.

There’s also the possibility of intermodulation distortion with high-resolution audio. Dennis Burger, senior editor of SoundStage! Access, sent me this fascinating article that’s long but well worth a read: “24/192 Music Downloads . . . and Why They Make No Sense.”

Third is where you’re listening. This is probably the least important of these three caveats, but is still worth mentioning. High-rez, lossless audio is very data-intensive. Not as much as video, of course, but a lot more than compressed, lossy audio. Generally, this isn’t a huge deal, but if you have data limits, stream a lot of music, or you’re regularly in areas where data speeds are reduced, you’ll either have issues like dropouts, run up against your data cap, or get dropped down to lossy, lower-resolution versions of your chosen music. The aforementioned LDAC, and Bluetooth in general, will sacrifice quality to maintain a stable connection, for example.

Can you hear it?

Here’s the only important question: can you actually hear the difference between lossy-compressed, regular-resolution audio, and high-rez lossless? This is a very difficult question to answer, and anyone who says yes (or no) definitively without caveats should be viewed with skepticism. It’s not as easy as switching between two versions of a song (or two output resolutions) on a streaming service, as there’s no guarantee they’ll use the same source files. There’s no guarantee there’s nothing else done differently to the two files either, apart from the resolution and type of data compression.

So after all that, here’s the nuance. If your equipment is capable of playing high-rez audio, and it’s not getting muddled by Bluetooth, and you don’t have any data limitations, then sure, it’s great to start with the highest-quality stream available. Don’t feel it’s vital in every situation, however. Modern lossy compression is very, very good, and has been for many years. It shouldn’t be viewed with the fear and disgust that early compressed audio received (somewhat fairly, in my opinion). After all, isn’t the point to enjoy the music? Isn’t the music the thing? I’d take an MP3 of my favorite song encoded in the ’90s over silence, and the horrors of my own thoughts, anytime. How about you?

. . . Geoffrey Morrison