I’ve been writing audio product reviews for 30-plus years, and reading them for about 45 years, and there’s one question none of them have ever addressed—but that I, and many of my readers over the years, have often wondered about. Sure, the most dedicated reviewers can do thorough, informed evaluations of a product. But how do they know that what they heard is representative of what a reader buying that product will hear? We almost always get just one product sample—maybe, in unusual cases, two. But from Julian Hirsch to the 18-year-old reviewer who just started his own TikTok channel last week, we all assume—or perhaps more accurately, hope—that the sample we tested is representative of the ones our readers buy in a store or online.

Skullcandy Jib earphones

Skullcandy Jib earphones

Of course, manufacturers don’t budget for sending, say, ten samples of a product so a reviewer can test them for consistency. Nor would the reviewer be wise to trust that the manufacturer hadn’t put them all through an extra round of QC before shipping them, or that ten samples that are likely from the same production run are comparable in performance to samples from a later production run. And in an era where it’s much tougher to make a living wage from reviewing than it was in Hirsch’s day, no reviewer has the time to evaluate (and unpack, set up, and repack) nine additional products.

However, I recently stumbled upon an opportunity to do at least a cursory examination of the consistency of a few headphones and earphones—and while my tests were necessarily very limited, I did come to a couple of interesting and useful conclusions.

JustJamz earphones

JustJamz earphones

My chance arrived when I was tasked with testing the maximum volume of a bunch of cheap headphones marketed to schools. Audio/video programming is an essential part of modern education, so kids may find themselves wearing headphones for an hour or two a day, and we wanted to find out whether or not those headphones might present the risk of hearing damage.

Some of these headphones were available only in lots of five, ten, or more, so in those cases, I ended up with extra samples I didn’t need. But then it dawned on me—why not test these headphones to see how consistent they are? If headphones that typically cost between $4 and $15 each are pretty consistent—well, that wouldn’t prove that the more expensive models we review here on SoundStage! Solo are equally reliable, but it might ease our doubts a little.

Learning Headphones LH-55 (lower left) and Avid AE-36 (top right) headphones, with Skullcandy Jib earphones

Learning Headphones LH-55 (lower left) and Avid AE-36 (top right) headphones, with Skullcandy Jib earphones

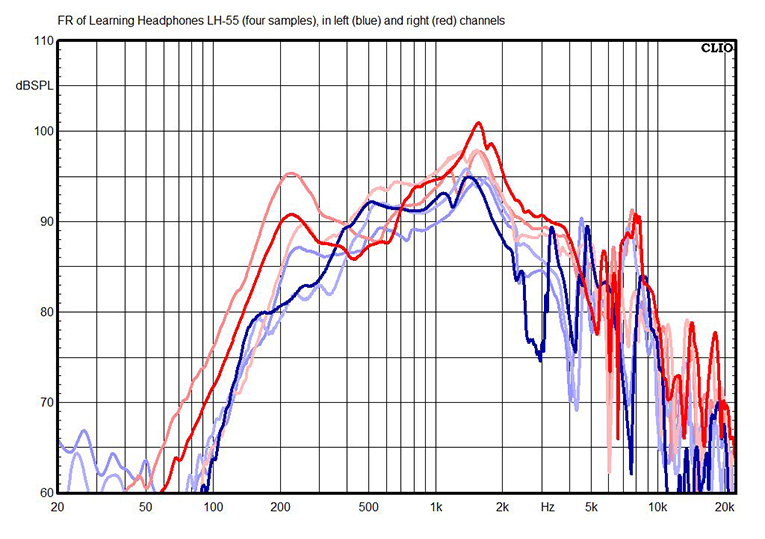

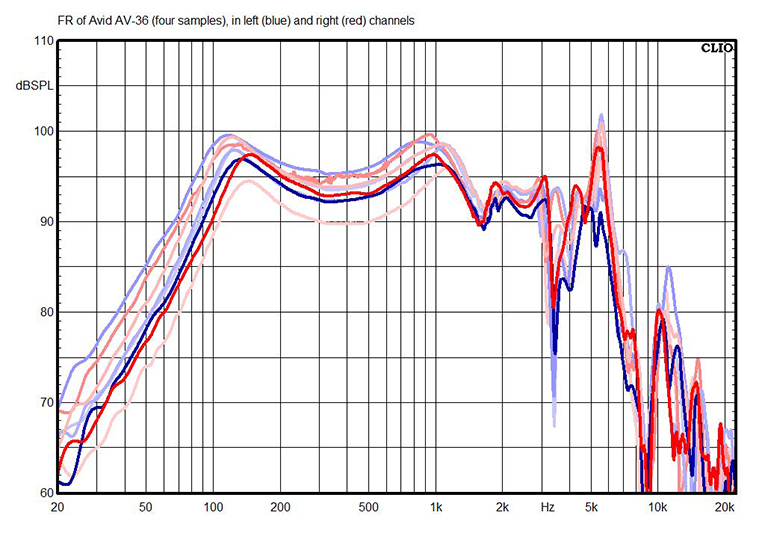

The two headphones I received in mass quantities were the Learning Headphones LH-55 (a generic over-ear model costing $3.75 each) and the Avid AE-36 (a much nicer model equipped with a boom microphone and selling for $13.95 each). Because my Audiomatica Clio 12 QC analyzer can show only eight measurements at a time, I decided to measure just four sets, so I can show you how consistent (or inconsistent) the frequency response is, and how well the left and right channels match. I put the first sample in dark blue (for left channel) and red (for right channel), and the following samples in lighter shades so you can see how consistent the results are.

The LH-55 headphones resemble (and may be identical to) some of the ultra-cheapo headphones that airlines hand out to fliers who aren’t cool enough to bring their own cans onboard. The frequency response is a mess—basically a giant peak around 1.5kHz—and it also seems inconsistent from sample to sample. This isn’t surprising; because these are small on-ear headphones, it was almost impossible to get them to seat consistently on the GRAS Model 43AG ear-cheek simulator I used for these measurements. Whether the issue stems from positioning inconsistencies or manufacturing inconsistencies, I can’t say—but does it really matter?

The Avid AE-36 headphones fared far better. While these are also on-ear headphones (at least for adults and the Model 43AG’s simulated pinna), they are larger and thus achieve a more consistent seal on the ear. Other than one right-channel measurement that’s about 5dB lower than the others (indicating poor driver matching), the AE-36 ’phones’ consistency looks pretty good, especially for the price.

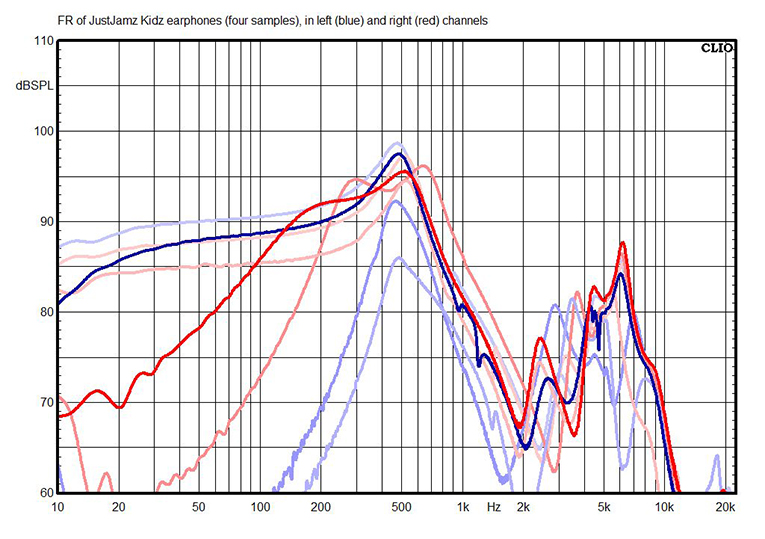

I wanted to look at a couple of earphones, too, but unfortunately, we hadn’t ordered any of them for testing. So I just bought some myself. I started with the JustJamz Kidz earbuds, which, at $1.79 each, are clearly intended for applications where kids are likely to lose or break them.

Sonically, the JustJamz were reminiscent of some of the garbagephones I encountered in my recent exposé of truck-stop earphones, with huge peaks at 500Hz (where most earphones might have a dip) and 6kHz. Because I used only my RA0402 ear simulator for the earphone measurements—instead of the full Model 43AG with simulated pinna—positioning wasn’t a concern, because it’s very easy to get consistent results when pushing the earphones’ round silicone tips into the conical stainless-steel cylinder of the RA0402. That’s my way of saying that the colossal differences in bass response appear to be a result of the JustJamz earbuds’ wild sample-to-sample inconsistencies rather than any measurement incompetence on my part. It seems there was zero effort to get consistent performance from the JustJamz—although I do have to concede that sound did come out of all the samples I tried, so that’s something, I guess.

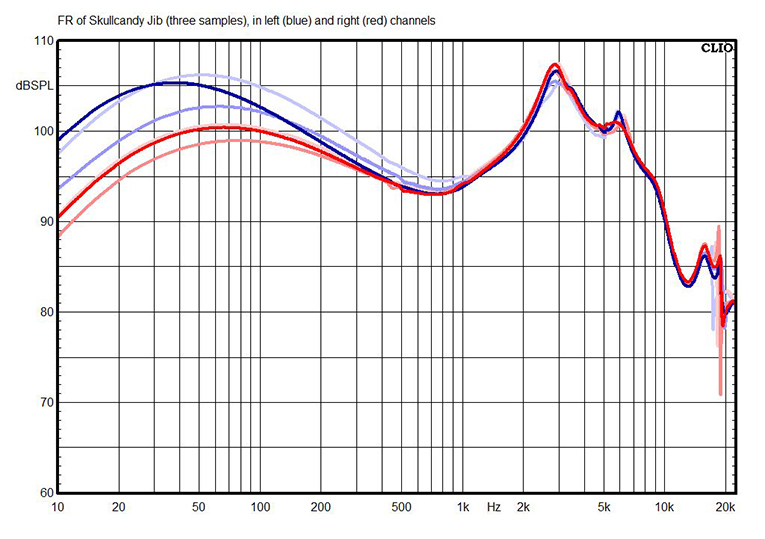

After seeing the lousy results of the JustJamz, I wondered what I’d get by collecting a few samples from a major brand. I chose the $9.99 Skullcandy Jib earphones because I’d heard good things about them, and because I could easily round up three samples from different sources: Amazon, plus my local Best Buy and Walmart. Not only did the Jibs exhibit an admirably normal-looking frequency-response curve, but the consistency above 1kHz was outstanding. It wasn’t so good at lower frequencies, and as I stated above, any inconsistencies measured with the RA0402 ear simulator are likely due to the product rather than to sloppy measuring technique. But my guess is that these differences in response from model to model and from left channel to right wouldn’t be all that noticeable.

So what can we conclude from this exercise? In one sense, nothing—even with the most expensive headphones, we can’t be sure what the manufacturing tolerance is or how diligent the manufacturer is about quality control. But it does appear to me—at least from this extremely small sample—that while we can’t expect consistency from the ultra-cheap, bottom-feeder generic products out there, once a better-known company slaps its name onto a set of headphones or earphones, it’s likely the model that we review here on SoundStage! Solo will be reasonably similar to the one you buy.

. . . Brent Butterworth