The Harman curve—the well-known, science-based “target curve” for headphone and earphone frequency response—has been with us for almost a decade. Yet it seems more controversial than ever, and a group of audio enthusiasts who could be called “Harman curve haters” has emerged. I knew this phenomenon existed on some level, but I started to realize how prevalent it has become only after I recently reviewed the Apos Audio Caspian headphones. The Caspians were voiced by a reviewer/consultant named Sandu Vitalie, who describes the Harman curve as sounding “soulless and boring.”

Elsewhere, I’ve seen the Harman curve tarred with adjectives such as “artificial,” “plastic,” and “unrealistic.” I’ve seen it criticized for sounding too hot in the upper midrange—and for sounding too laid back in the upper midrange. In an online poll of 157 audio enthusiasts, 68.8% expressed a negative opinion of the Harman curve.

Sean Olive has been in charge of most of the Harman-curve research

Sean Olive has been in charge of most of the Harman-curve research

As I read the countless online comments about the Harman curve, I’m happy to see some well-reasoned objections, some of which square with my decade of observations based on measurements, my own listening, and comments from panelists in multiple-listener tests I’ve conducted or participated in. But I’m saddened to encounter less-rational criticisms from enthusiasts and reviewers who don’t seem to have read any of the research supporting the Harman curve—and in some cases, who don’t seem to have read much about audio other than product reviews and comments on internet forums.

I thought it might be valuable to examine some of these criticisms in an effort to move the discussion a notch closer to a fair assessment of this research.

First, a quick backgrounder

When the Harman curve headphone research began, around 2010, the science of headphone design dated back about three decades, to an era before computer-based measurements, and it was long overdue for a refresh. Inspired by the emergence of a headphone boom (itself triggered by the invention of the smartphone), scientists at Harman International (parent company of JBL, Harman Kardon, Mark Levinson, Revel, and numerous other audio brands) began conducting blind listening tests to see what type of headphone and earphone sound most people prefer, and if such preferences correlated to measurements of headphone and earphone characteristics.

The research expanded to listening tests involving hundreds of listeners and products, and resulted in 15 (by my count) research papers, reviewed and published by the Audio Engineering Society. As I’ve found in my interviews with headphone designers, other companies, such as PSB and 64 Audio, arrived at similar curves through their own research. And some popular headphones, such as the Sony MDR-7506es, were voiced similarly to the Harman curve many years before the Harman research was published.

Now let’s consider some of the criticisms of the Harman curve that have emerged. I’ll list them in what seems to me to be the order of validity, with the most rational claims presented first.

1) The Harman curve is fine for average listeners but not for audiophiles.

There’s some validity to this idea, in the sense that audiophiles may want to hear music differently than most listeners do. Companies such as Etymotic, Grado, and HiFiMan won over audiophiles with a focus on products that deliver a bright tonal balance, emphasizing treble and attenuating bass. The extra treble tends to create an enhanced sense of detail and spaciousness. Anyone who regularly hears real instruments in a live setting knows this tonal balance is not natural or accurate, and not faithful to the musicians’ intent, but if some audiophiles enjoy music more this way, that’s fine.

That said, the notion that audio enthusiasts are more sophisticated in their tastes or more accomplished in their listening skills than the listeners employed in the Harman research is way off base. For example, in the company’s main research project on earphone preferences, they used 71 listeners. From that group, 36 had their hearing tested and had passed level eight in the Harman How to Listen training software—and the fact that they completed such a demanding process suggests they had a strong interest in audio and music. On the other hand, I’d guess that few of the Harman curve’s critics have recently had their hearing tested, and probably none could get even half as far through Harman’s training without investing a lot of hours in the effort. Any audio enthusiast who wants to throw shade at Harman’s listening panel should first download the How to Listen software (it’s free), see what level they can get up to, and share a screenshot of their results along with their criticisms of Harman’s methods.

Let’s not forget that the Harman listening tests were done blind, so the listener’s attachment to certain brands couldn’t be a factor—something that no one doing sighted listening tests can plausibly claim. The notion that hundreds of listeners, in carefully controlled tests where the product identity was concealed, would prefer sound that was “artificial” or “plastic” is an extraordinary claim that must be supported with extraordinary evidence to be taken seriously.

2) Everybody hears differently, so an average preference curve can’t work.

This notion is true to some extent because everyone has some natural variation in the physical shape of the ear canal, pinnae, etc., and almost everyone’s hearing has been damaged—from slightly to severely—by exposure to loud sound.

I’ve been conducting multiple-listener tests since the early days of my career, more than 30 years ago. Probably more than any other audio writer working today, I’ve seen first-hand how listener responses to the same product can be substantially different. I’ve also made it a point to work regularly with younger listeners, such as Wirecutter headphone editor Lauren Dragan; she and I had our hearing tested during the same audiologist visit, and she can actually hear up to about 20kHz, while like most men my age, I top out somewhere around 12kHz. Lauren and I do differ in our opinions of headphones and earphones at times, and based on my measurements, I’ve found it’s typically due to things going on in the higher frequencies, where my ears are less sensitive; in particular, a few headphones and earphones that I love, she finds grating because she hears high-frequency peaks that escape my notice.

Interestingly, though, while headphones and earphones that come close to the Harman curve aren’t always the favorites among Lauren, me, and the listening panelists we’ve used in our testing, many Harman curve-ish models have ranked among our favorites, and I can’t recall a single one that listeners sharply criticized.

However, many audio enthusiasts seem to think the claim that “everybody hears differently” means there are radical, unpredictable differences among most people’s hearing, almost as if a gremlin inside everyone’s brain were using some sort of neural EQ to randomly boost some frequencies and cut others. Those enthusiasts often use this notion as an excuse to dismiss any statement about audio that they don’t agree with—but I’ve never seen one of them present data to support this idea, and I’ve never gotten the impression that they’ve done any serious study on the subject of human hearing.

In my work testing hearing aids and personal sound-amplification products (PSAPs) for the technical journal AudioXpress, I’ve had my hearing tested multiple times and interviewed several manufacturers and audiologists on the subject of hearing loss. I’ve learned that while people do sometimes lose hearing sensitivity in unusual ways, most hearing loss is characterized more by degree than by type. Typically, with age, we experience a decreasing ability to hear high frequencies, and often, the development of a so-called “noise notch” somewhere between 3 and 8kHz. People may react differently to some audio products because they have a greater degree of hearing loss, but within a chosen demographic, most people hear fairly similarly unless their hearing has been severely damaged. In fact, some hearing-correction technologies, such as Mimi, offer the option of using the listener’s gender and age to predict the amount of hearing loss.

What’s more, listeners’ preferences are actually far closer than audiophiles might expect. In the 2014 Harman paper “The Influence of Listeners’ Experience, Age, and Culture on Headphone Sound Quality Preferences,” a listening test involving 238 subjects in Canada, China, Germany, and the US, ranging in age from 20 to 70, the researchers found that “Listeners generally preferred the same headphones regardless of their listening experience, age, or country of residence.”

3) It’s just a bunch of scientists telling us what we’re supposed to like.

Anyone who’s read any of the Harman headphone listening test papers understands that this project was an effort not to tell listeners what they should like, but to find out what they like.

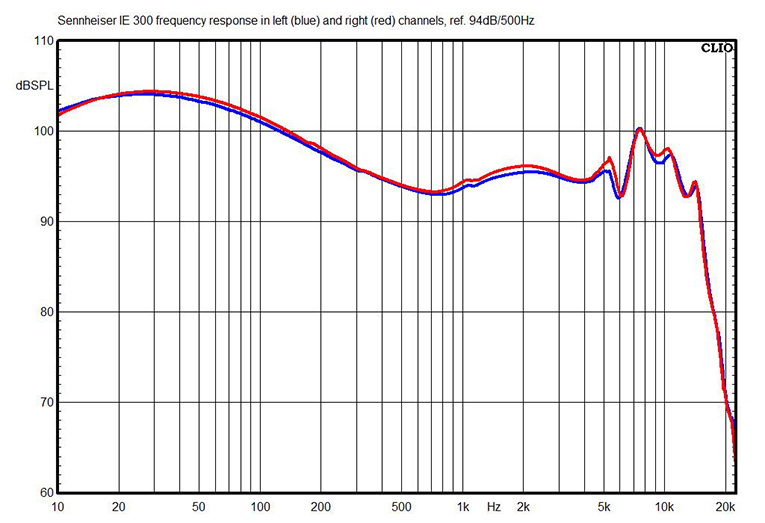

Let me state that some headphones and earphones I like fall well outside the Harman curve. Most open-back planar-magnetic models, such as those from Audeze, Dan Clark Audio, HiFiMan, and others, have a much flatter bass response than mandated by the Harman curve, but I still like ’em, and most other reviewers and enthusiasts seem to, too. I’ve recently found a couple of earphones I very much enjoyed—the Campfire Audio Holocenes and the Sennheiser IE 300s—that have a flatter midrange response than the Harman curve, with much less energy around 3kHz.

I assume Harman began its research as a way to help its headphone brands (AKG, Harman Kardon, and JBL) tune products in a way that would win customers’ approval and increase sales. But the research is equally useful for consumers, most of whom just want to buy headphones or earphones voiced in a way that’s likely to sound good to them, without investing a colossal amount of effort into their selection process. Sure, no matter how a product is voiced, you’ll find someone who doesn’t like it—although we can’t know if that dislike is because of a legitimate objection to the sound or to biases associated with the brand, the design, the technology, or the price.

It’s also important to note, as I did in my 2019 article about the Harman curve, that there are three variants of the curve to allow for varying tastes and hearing characteristics.

Whether headphones or earphones voiced along Harman curve guidelines will be any one listener’s favorite, we can’t say for sure, but once you take the above-noted biases out of the equation, the research shows the majority of listeners will like them. The fact that many headphone enthusiasts object to the Harman curve—in highly biased sighted testing where no controls are in place—probably says more about group dynamics and consumer psychology than it does about audio.

4) The Harman curve sounds “artificial” or “boring” or . . .

Criticism of the Harman curve—or anything else in audio—that relies entirely on non-specific adjectives can be dismissed out of hand. Because it’s reasonable to assume people will lead with their best argument, it’s reasonable to assume the commenter who merely slings derogatory adjectives has nothing more intelligent to say on the subject—which suggests they haven’t amassed much knowledge or experience, and that their comments are unworthy of the reader’s attention.

When audio enthusiasts present only non-specific adjectives in their critiques, they’re making an appeal to authority—presenting themselves as the authority, because they offer no evidence to back up their assertions. Appeals to authority sometimes have merit; if Chris Potter says a saxophone sucks, then maybe it does. But the person presenting themselves as an authority must have considerable and easily demonstrable expertise on the subject, especially if they’re criticizing the work of scientists whose CVs show decades of experience and countless publications.

Even if a Harman curve hater does make a specific criticism—e.g., the upper mids are too hot or too laid-back—they need to present reasons why we should respect their statement. If they think the Harman curve has too much bass, they have to tell us how they know the Harman curve has too much bass (and specify which version of the Harman curve they think has too much bass). Ideally, what I’d love to see is a well-reasoned technical argument backed with scientific data, such as measurements, controlled listening tests, and citations of existing scientific and technical publications.

In lieu of that, I’d at least like the commenter to list some reasons I should take them seriously. These might include professional experience in audio production or product development; substantial and recent experience in music performance or recording; or documented experience in audio product measurement or audio-related fields, such as acoustics, audiology, or psychology. Anyone who wants to be taken seriously as an audio expert should be able to point to, say, a LinkedIn page that lists their experience and accomplishments, or a Bandcamp page that highlights some of their recording work or performances, or maybe a web page that shows some of the pro-level systems design work they’ve done. Listening casually to a few headphones, gabbing anonymously on audio forums, reading audio product reviews, starting a blog or YouTube channel, or messing around with amateur measurement gadgets won’t cut it.

I hope this article might inspire some of the Harman curve haters to raise their game—confirming their contentions with their own controlled testing, making specific and detailed critiques of where Harman gets it wrong, and publishing and presenting their results so they can be critiqued in public forums. If they really know better than the Harman scientists do, and can make more useful recommendations, I’m confident that the audio industry will be interested. But it’s gonna take a lot more work than slinging a few adjectives.

. . . Brent Butterworth