Running measurements of speakers and headphones on a regular basis teaches you many things about audio that you’d probably never otherwise learn, but it has a side benefit I haven’t seen discussed: it lets you monitor your hearing. The tests, which involve tones played through the devices under test, typically start at the high frequencies and run down to the low frequencies, and as your hearing degrades with age, you see more and more numbers tick away on the display before you can start to hear the tones.

Still, since the early 2000s, I’ve had my hearing tested every four years or so -- usually when I was going to an audiologist to have molds made for custom earphones. A few months ago, inspired by a couple of way-too-loud big band rehearsals (where I was facing the horns instead of standing behind them, as the bass player usually does), I visited Dr. Julie Glick, a Los Angeles audiologist, to get some custom-molded musician’s earplugs, and got a hearing test while I was there. Glick has a reputation as a sort of “audiologist to the stars” because she works with many professional rock musicians whose hearing is in danger or already damaged. Unlike almost all audiologists, Glick tests hearing at frequencies up to 20kHz; most audiologists stop at 8kHz because higher frequencies aren’t relevant to speech comprehension. She provides a separate chart to show the high-frequency results.

Hearing loss accumulates as we age, and eventually everyone experiences some of it. It’s worse in males. According to a 2008 study conducted by John Hopkins University, men are five and a half times more likely than women to develop hearing loss as they age, starting as young as 20. Most audio reviewers are male, and many are in their 50s, 60s, or 70s, which means many, perhaps most, audio reviewers have significant hearing loss.

Yet the only time I can remember seeing this topic addressed honestly is in the remarkably frank farewell note of former InnerFidelity editor Tyll Hertsens upon his retirement. “My ears are going,” he wrote. “They are pretty good for a 60-year-old . . . well, my left ear anyway. But hearing tests have shown the trend. It’s just not good enough anymore, IMHO, and getting worse.”

In section 3.2 of Sound Reproduction: The Acoustics and Psychoacoustics of Loudspeakers and Rooms, esteemed audio researcher Floyd Toole explains how hearing loss can affect someone’s impressions of an audio product. His examination of the subject goes back to a 1982 study done for the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation, in which loudspeakers were evaluated by a group of people including many audio professionals, some of whom had some level of hearing damage -- an occupational hazard for them.

Some of the testing involved numerous repeated blind evaluations of the same speaker. The researchers found that listeners who gave the least-consistent ratings of these speakers -- who might like a speaker in the morning but dislike it in the afternoon -- tended to have hearing loss. As Toole puts it, “Without the ability to hear small acoustical details in music and voices (good things), or low-level noises and distortions (bad things), these people were handicapped in their ability to make good or consistent judgments of sound quality, and this was revealed in their inconsistent ratings of products. It did not prevent them from having opinions, deriving pleasure from music, or being able to write articulate dissertations on what they heard, but their opinions were not the same as those of normal hearing persons.”

I became aware that my hearing was affecting my evaluations way back in 1997, when I conducted a series of double-blind tests for Home Theater magazine comparing Dolby Digital with DTS. Although I was only 35 at the time, I was one of the three oldest listeners in those tests, and I noted that the listeners in their 20s consistently cited DTS as having superior high-frequency spatiality. Try as I might, I couldn’t hear what they were describing, but three of them, in isolated blind testing sessions, described the same effect, so I figured there must be something to it.

A few years later, when I worked for Dolby Laboratories and gained a more in-depth understanding of audio codecs, I realized the younger listeners were hearing the channel coupling that Dolby Digital uses (and DTS, at the time, did not). Above a certain frequency (typically higher than 10kHz), Dolby Digital and many other codecs encode the high-frequency sounds from all channels into a single mono channel to save data, and on playback distribute this mono high-frequency information back into the five or more channels in the same per-channel proportion as the original -- so the level of high-frequency information in each channel is preserved, but the content in each channel is the same. This is a wise sacrifice, because it’s better to cut out those bits in the upper treble than in the midrange, where anyone could hear it. Even at 35, an age at which I could ace a standard hearing test, I couldn’t hear the coupling -- but the younger listeners could.

Ever since then, whenever time and resources have permitted, I’ve brought in younger listeners to get their opinions of the audio products I test. I do this now, with SoundStage! Solo’s tests of headphones and earphones, where I bring in listeners who are experienced in audio, but around 40 years old. To me, it’s an ideal combination: young listeners who have the best hearing, and an older listener (me) whose experience in measurement and work in audio product development and tuning allow him to translate what they say into consistent descriptions of a product’s sonic characteristics -- and accurate diagnosis of its flaws. Interestingly, I’ve noticed during the countless blind comparison tests I’ve conducted that even when the younger listeners describe the bass, mids, and lower treble of an audio product roughly the same way I do, they sometimes describe a higher-frequency coloration that was inaudible to me. I’m glad I have them around -- and that I have measurement gear on hand to confirm (well, usually) our descriptions of a product’s sound.

My hearing test results weren’t bad for a 57-year-old man, but they definitely showed I’m not hearing things my younger colleagues can. According to Dr. Glick’s report, “Audiometric test results reveal hearing within normal limits with a mild sensorineural hearing loss from 3kHz to 6kHz in the left ear only. Speech discrimination is excellent bilaterally.” What she’s describing is the “noise notch,” a reduction in sensitivity, usually centered at about 4kHz, that’s essentially “wear and tear” on the ear. This notch is the most common kind of hearing loss, and it tends to develop earlier in males than females. I knew from previous tests that my right ear’s better than my left, but was a little surprised to see the noise notch deepening in my left ear but not in my right -- especially when I don’t notice an imbalance between the two ears, as mono images at all frequencies still sound dead centered whether I’m listening to speakers or headphones.

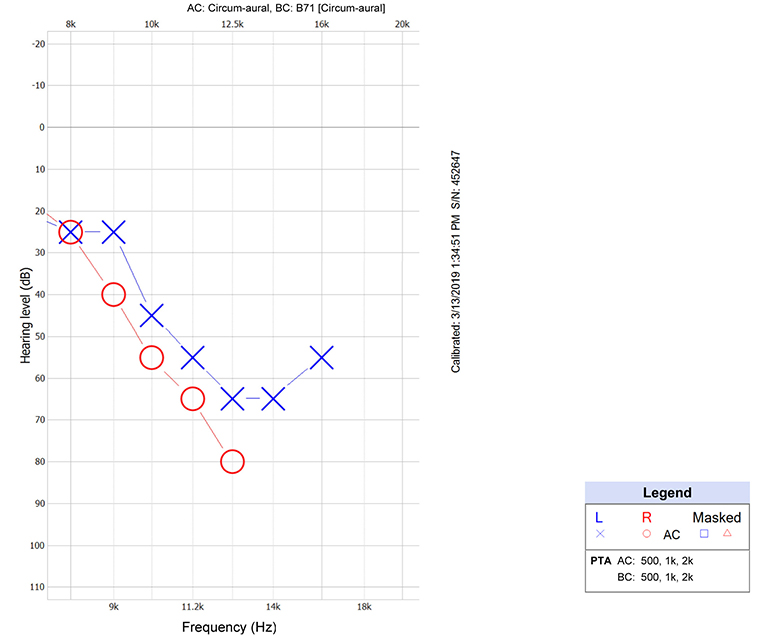

Sadly, Dr. Glick’s tests show most of the upper octave (10kHz to 20kHz) of treble is something I’ll never again experience. I’ve included the special audiogram she does for frequencies above 8kHz. As you can see, my hearing sensitivity starts to decrease significantly above 10kHz. I wasn’t entirely sure what the chart means in real-world terms, so I ran a quick test using the Audio Tool app on my Samsung Galaxy S9 with Direct Sound Serenity II headphones. I was surprised, after seeing the chart, that I could still easily hear a sine wave at 12.5kHz, although it sounded several decibels quieter than the 10kHz sine wave I tried. The sound was getting really quiet by 12.8kHz, and at 13kHz, I’m not sure I could hear anything at all.

The good news is, even with normal amounts of hearing loss for my age, I can still easily hear and identify, for example, the common (and most troublesome) flaws in speaker designs -- such as poorly chosen crossover points and slopes, unwise driver positioning, cabinet resonances, and questionable port tuning. I know only a few younger listeners who can do this, all professional speaker designers with around 20 years of experience. My ears can quickly tell if a headphone or speaker is tuned according to generally accepted principles, or merely to its designer’s whim.

Most important, I can still appreciate the great audio products . . . and despise the bad ones. And I think all but perhaps the oldest (or most hearing-impaired) audiophiles can say the same.

But if headphones are distorting at, say, 7kHz -- in which case the lowest distortion harmonic would be at 14kHz -- I can’t detect it without the help of either an audio analyzer or a younger listener. Serious audio product reviews should include one or, preferably, both.

. . . Brent Butterworth